Let's Talk about Rembrandt and his Orient

On 14 October, renowned art historians Gary Schwartz and Arnold Vrolijk gave a joined Museum Talk on the exhibition Rembrandt's Orient: West Meets East in Dutch Art of the Seventeenth Century and the history of Oriental Studies at Leiden University.

In the first part of the lecture, Gary Schwartz, the guest curator of Rembrandt’s Orient, presented the exhibition focusing on some of its highlights. Gary Schwartz is an art historian specialised in Dutch and Flemish art with numerous publications on Hieronymus Bosch, Rembrandt van Rijn and Johannes Vermeer. In 1998 he founded CODART, an international network of curators of Dutch and Flemish art. Schwartz’s presentation was followed by a lecture by Arnold Vrolijk, the curator of Oriental Manuscripts and Printed Works at the Leiden University Libraries. He addressed critical issues regarding Rembrandt's influences from printed images of the Orient and the development of the Oriental Studies in Leiden.

The Orient, an umbrella term for the non-Eastern world including the Levant, Eastern Mediterranean, and Asia, fired the imagination of Dutch artists of the seventeenth century. With the expansion of the Dutch trade and the circulation of goods worldwide, people's fascination for the Eastern culture influenced the contemporary lifestyle and fashion. At that time, Dutch artists used plethora of oriental motifs, costumes and ornaments in portraits, still lifes, history scenes and biblical scenes

With Rembrandt as a starting point, Rembrandt's Orient: West Meets East in Dutch Art of the Seventeenth Centuryexamines the meeting of the two worlds represented through the eyes of Dutch artists. The exhibition opened first in the Kunstmuseum Basel in October 2020 and in March 2021 in the Museum Barberini in Potsdam and presented more than 100 works of prestigious Dutch artists like Rembrandt, Jan Lievens, Ferdinand Bol, Jan van der Heyden, Willem Kalf, and Aelbert Cuyp. Oriental costumes and motifs appear in biblical scenes, still lifes, but also individual and group portraits (see fig. 1). Amongst the exhibition's highlights are Rembrandt's tronies (a tronie is a portrait study of a certain expression or appearance)

which gained popularity and developed into an independent art form during Rembrandt's time (see fig. 2, 3). Visitors can still see the exhibition online in a 360° digital tour at the Museum Barberini and Kunstmuseum.

But what were the primary sources on which Rembrandt based his depictions of the Orient? And how are these sources related to the development of Oriental Studies in the Netherlands, and Leiden in particular?

As Arnold Vrolijk explained in the second part of the lecture, although it is known that Rembrandt studied at Leiden University at the faculty of Letters, his academic background is still uncertain. There is no evidence that the artist followed any lessons of Oriental studies or that he had access to or even knew about the collection of Oriental manuscripts at the university library as a student. So, where could Rembrandt have seen pictures of the East? The artist likely obtained numerous sixteenth-century prints of scenes, buildings, and people from the Ottoman Empire drawn after life during ambassadorial journeys.

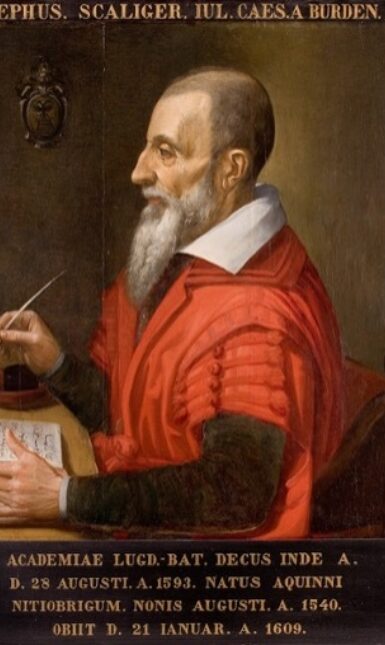

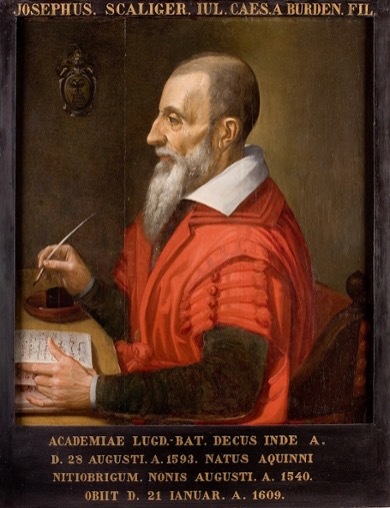

Arnold Vrolijk also discussed the birth of Oriental Studies at Leiden University. The first collection of Oriental manuscripts entered Leiden University in 1609 after the death of the Protestant Orientalist scholar Joseph Justus Scaliger (see fig. 5), who had moved to Leiden during the French religious wars. A few years earlier, Franciscus Raphelengius had become the first professor of Arabic at Leiden University. As the Dutch Republic arose as an independent power, strong diplomatic relations and commercial privileges with the Ottoman Empire were established. The Dutch exchange with the Ottoman Empire gave an impulse to the development of Oriental scholarship in the Republic and at Leiden University, which flourished as a significant centre of Oriental studies in Europe, and continues to do so.

ISMINI KYRITSIS is a student of the MA Museums and Collections at Leiden University. Her interests include Early Renaissance Dutch and Golden Age art, museology, and collecting strategies, especially contemporary collecting.

1 Comment

Thanks for your blog, Ismini! For those who want to re-watch the Museum Talks of Gary Schwartz and Arnoud Vrolijk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lef9jPaVvn4