Beautiful and Bizarre: ‘Body Language’ at Museum Catharijneconvent

St Mary Magdalene almost fully covered in hair, saints carrying their own heads, Christ’s wounds in the shape of a vulva, and nuns picking phalluses from a tree. See all this and more at the exhibition “‘Body Language’: The Body in Medieval Art” at Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht.

This intriguing exhibition at the Catharijneconvent in Utrecht is an experience for the senses and imagination, and shows a side to medieval art we rarely see. From the first instance it is clear that the artworks one sees in this exhibition are representative of how people during the Late Middle Ages (the exhibition uses the timeframe c. 1300-1500) looked at and thought about the human body. If anyone still has the idea that this period was dark and people were prudish, they will probably change their opinion after having visited this exhibition.

The first artwork one encounters is a crucifix from c. 1350 (fig.1). The image of Christ on the cross was very popular during the Middle Ages, but this particular sculpture is interesting because it shows not only the stigmata on the hands, feet and right side, but also many smaller, round wounds on the torso, from each of which three streams of blood seep. All these smaller wounds symbolise the bubonic plague, also known as the Black Death, which was raging through Europe at the time this sculpture was made. The three streams represent the Holy Trinity – the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Medieval people would presumably find consolation in this artwork, for Christ, too, is experiencing the plague. By placing this sculpture at the very beginning of the exhibition, the curators, Annabel Dijkman and Wendelien van Welie-Vink (guest curator, affiliated with the University of Amsterdam), have not only made it clear how people from the Middle Ages humanised their religious artworks, but also stress how relevant these artworks are for our current times.

The exhibition is categorised in themes, amongst which are ‘blood’, ‘hair’, and ‘the breast’. Some of the installations are somewhat distracting, in particular the gallery displaying works of art related to blood, with its bright red lights and sounds of dripping blood. On the other hand, some may find these dramatic tactics enhance the museum-experience. I was happy to see several personal favourites displayed, such as St Valérie holding her head (fig. 2) from Musée du Louvre.

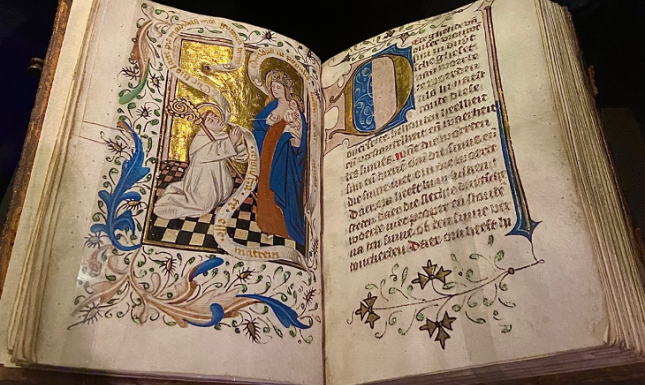

I was, however, happier to discover so many pieces unknown to me, a painting of St Mary Magdalene as a hairy wild-woman (fig. 3), the story of St Bernard of Clairvaux receiving the Holy Virgin’s breastmilk when he is ill (fig. 4), and Christ being pressed by His cross on a grape press (fig. 5) for instance. The latter symbolises the wine one drinks when receiving the Eucharist; which of course symbolises the blood of Christ.

Although the Catharijneconvent was able to display masterpieces from Musée du Louvre, Musée de Cluny, and Rijksmuseum, other artworks could not travel to Utrecht due to the coronavirus, and reproductions have been provided. Nevertheless, the exhibition consists of masterpieces of illuminated manuscripts, panel paintings, and sculptures.

‘Body Language’ shows how images we now might think peculiar were created to bring people closer to their religion, closer to God. The exhibition contributes greatly to our understanding of the minds of people from the Late Middle Ages, and the way they practised and, most importantly, humanised their faith. The exhibition is on view until 17 January 2021. Link to the exhibition’s page on the museum’s website, where one can reserve a timeslot: https://www.catharijneconvent.nl/tentoonstellingen/body-language/. An exhibition catalogue (in Dutch and English) is available for purchase for 29,95 euros. The museum has taken all the corona-measurements as instructed by the RIVM into account.

Justus F. C. Schokkenbroek is a second-year student of Art History at Leiden University. His main fields of interest are Late Mediaeval arts and architecture, Italian Renaissance art, and Asian arts and cultures, particularly of South and Southeast Asia. Contact: j.f.c.schokkenbroek@umail.leidenuniv.nl.

0 Comments