15.000 oysters, one pearl

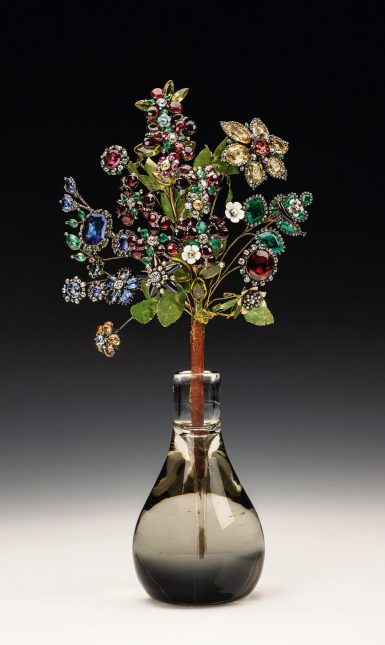

It's not a bad idea to take your sunglasses to the 'Juwelen!' (Jewels!) in the Hermitage Amsterdam exhibition, because the diamonds, rubies, emeralds and brilliants on display are shimmering and shining like the sun.

'Juwelen!' (Jewels!) in the Hermitage Amsterdam is all about the riches, opulence and luxury of the Russian nobility. Visitors get a peek into their aristocratic lives full of glitter and glamour by seeing the most precious objects of tsars, tsarina's and their friends and family. The exhibition is put together in collaboration with the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg, who generously lent out a selection of their rich collection to their namesake in Amsterdam. The collection holds pieces spanning from Peter the Great until the last Tsar and Tsarina of Russia: Nikolai II and his wife Tsarina Alexandra Fjodorovna.

When walking through the exhibition it looks as though pearls were growing from the trees in the czarist empire. However, until the end of the 19th century, they were very rare: to find one pearl, one needed to open 15.000 oysters. This illustrates the enormous wealth of the Russian nobility, something they were more than happy to demonstrate.

The exhibition starts in a great ballroom, where Tchaikovsky is playing in the background. Pieces of jewellery are exhibited together with the costumes that were worn to actual balls. They are also accompanied by portraits that show how the pieces were worn, like the portrait of Princess Zinaida.

To the visitor from the 21st century, some portraits might have more likeness of heavily decorated Christmas trees than of actual people. But in the czarist empire, the jingle was all about more is more. Jewellery was important within the social lives of the nobility because it told stories about their taste, political preferences, love life, status and family life. Fascinating is that not only the beauty of the pieces but also the histories behind them, still get across in this day and age. This is thanks to the wall-texts, clear object descriptions and the comprehensive audio tour, that tell about the different purposes of the pieces.

The function of jewellery was, among other things, to show off the prosperity of the family. A ball is the perfect public place to demonstrate this. However, the exhibition is not only about the public lives of the Russian aristocracy. It also shows the role of jewellery in a more discreet and secluded context. Therefore, the ballroom is followed by more private spaces, such as the boudoirs of the Winter Palace. Here sex, marriage, vanity and mourning, all parts of (every aristocrat) life, are shown as sources of inspiration for the design. This was expressed through, for example, the use of hair in a piece of jewellery. For instance, a widow could keep a lock of hair of her deceased husband in a locket, as to always keep her loved one close.

As a visitor, it is easily imaginable how the precious objects were handled and worn by the aristocrats. This is because the objects had such a highly functional role within their lives, which makes history more tangible for the 21st-century viewer. An example of this is the jewel casket from Augsburg. A key is hidden in the lid. One can imagine that the possessor of the casket would open it carefully, and then select which of the valuables inside would match well with his or her costume that night.

As the director of the Hermitage Amsterdam, Cathelijne Broers, states in the catalog accompanying the exhibition, jewels are much more than just eye-candy. This message comes across clearly in the exhibition, thanks to the aforementioned object descriptions, the audio tour and also the beautifully designed catalog. Curious about the intrigue, secrets and rich stories behind the hundreds of glittering pieces on display in the Hermitage? The exhibition is on view until September 27th, and don't forget to bring your sunglasses! For more information about this exhibition visit the Hermitage website.

Berber Kommerij is a second-year Art History student at Leiden University. She is interested in all kinds of art, cultures, exhibitions and stories. Contact her at b.kommerij@umail.leidenuniv.nl.

0 Comments